What is California Probate?

Probate is a Court process required to manage a Decedent’s estate and distribute his or her assets. Probate is statutorily driven, meaning that much of the process is governed by the statutes/laws passed by the California legislature and set forth in the California Probate Code.

What happens during a California Probate?

During a probate in California:

1. The Decedent’s assets are identified and marshaled by the Executor/Administrator;

2. The Decedent’s heirs/beneficiaries are determined;

3. The Decedent’s creditors are identified and his/her debts paid;

4. The Decedent’s taxes (and the estate’s taxes) are paid;

5. The estate’s assets may be liquidated;

6. The Decedent’s Executor/Administrator is paid;

7. The Executor/Administrator’s attorney is paid; and

8. The Decedent’s assets (or net liquidation proceeds) are distributed to his/her heirs/beneficiaries.

When is Probate Required in California?

With certain limited exceptions, a California Probate is Required when:

1. The Decedent was a California Resident;

2. The Decedent owned property in California; and

3. No “exemption” exists to avoid a probate.

How to avoid California Probate Court? (California Probate Exemptions)

Certain assets are exempted from probate and are, therefore “non-probate property”. Examples of “non-probate property” include:

- Assets titled to the Decedent’s revocable living trust;

- Assets held by the Decedent and another individual jointly, provided the Decedent is the first to pass away;

- Assets held by a husband and wife as “community property with right of survivorship”;

- Real property (i.e. real estate) transferred by way of a “revocable transfer on death deed”;

- Assets that name a “payable on death” or “transfer on death” beneficiary;

- Manufactured homes and mobile homes, provided they are on rental land;

- Automobiles and boats registered in California; and

- Assets remaining that, in the aggregate, have a value of less than $184,500 (in 2023).

For comparison, examples of “probate property” include:

- Real property (i.e. real estate) titled in the Decedent’s name without a “revocable transfer on death deed” on record;

- Real property (i.e. real estate) titled in the Decedent’s name as a “tenant in common” without a “revocable transfer on death deed” on record;

- Assets in the Decedent’s name alone without a “payable on death” or “transfer on death” beneficiary; and

- Retirement accounts and life insurance policies that do not name a “payable on death” or “transfer on death” beneficiary.

- Business assets or professional practice assets

What are the different types of Probate in California?

There are varying levels of probate in California, including what are informally called “formal” probates, “summary” probates, and “ancillary” probates.

The probate required (if a probate is required at all), depends on location of and value of the “probate property”.

- A “formal” probate is the most time-consuming and expensive type probate. At a minimum, a “formal” probate may last 9 to 12 months. In addition, the cost of a “formal” probate is based on a percentage of the fair market value of the Decedent’s probate. Much of the information in this Probate Guide applies to “formal” probates. Click here to see the cost of probate in California.

- An “ancillary” probate applies when 1) the Decedent died a non-California resident, 2) the Decedent’s estate is being administered in the Decedent’s “home” state (i.e. outside of California), but 3) the Decedent owned property in California. The Court in the Decedent’s “home” state does not have jurisdiction of the property in California, so an “ancillary” probate must be opened in California to turn the California property over to the Executor/Administrator of the probate in the Decedent’s “home” state.

- A “summary” probate is a short/expedited probate in California that rarely incurs the high fees of a “formal” probate. If the Decedent’s “probate property” has an aggregate fair market value of less than $184,500 (in 2023), or the Decedent’s property is to pass to the Decedent’s surviving spouse, or where the Decedent intended to transfer his/her property to his/her revocable living trust but failed to accomplish such transfer, a “summary” probate may be available to the Decedent’s Executor/Administrator. Whether or not Court supervision is required for “summary” probates is a fact-specific analysis and is beyond the scope of this Probate Guide.

How Long Does the probate process in California usually take?

In most counties in California, the minimum time to wrap up a formal probate is approximately 8 months (i.e. 2 months to get a hearing date to have an Executor/Administrator appointed + 4 months for creditors to file a claim + 2 months to get a hearing to approve final distribution).

However, even a “simple” probate (e.g. one with few assets, few (if any) controversies, few (if any) creditors, and little (if any) taxes owed), takes 10 months, but more often closer to 12 months and in some counties even longer due to few judges handling many probates.

For comparison, a more “complicated” probate (e.g. where the Decedent had many assets / creditors / heirs/beneficiaries, unknown heirs/beneficiaries, was a defendant in a pending lawsuit, had significant taxes, etc.) could last years.

COMPARE: With a revocable living trust, a probate can be avoided, and therefore so can the delays often inherent in a probate. Unlike a probate, a trust is generally not subject to supervision by the Court. Therefore, a simple trust administration in certain situations might be wound up in a matter of weeks.

How Much Does Probate Cost in California?

Besides the hard cost expenses of a probate, such as filing expenses, publication expenses, probate referee fees, and the costs of maintaining and safeguarding the Decedent’s assets for the months/years during which a formal probate may remain open, 2 parties may receive fees in a formal probate:

- The Executor/Administrator; and

- His/her attorney.

These parties may receive 2 types of fees:

- Statutory fees; and

- Extraordinary fees.

The statutory fee payable to the Executor/Administrator and to his/her attorney is statutorily defined. This means that the probate attorney fees in California may be the same as all executors/administrators.

Specifically, each party may receive a fee equal to:

- 4.0% of the first $100,000 in asset value;

- 3.0% of the next $100,000 in asset value;

- 2.0% of the next $800,000 in asset value;

- 1.0% of the next $9,000,000 in asset value;

- 0.5% of the next $15,000,000 in asset value; and

- For estates larger than $25,000,000 in asset value, the fee to the Executor/Administrator is determined by the Court.

For “extraordinary” services provided to the estate (e.g. services generally above and beyond the routine services an Executor/Administrator/attorney provides to the estate), the Court may award extraordinary fees, which are often based on an hourly rate.

COMPARE: With a revocable living trust, a probate can be avoided, and therefore so can the burdensome costs discussed above. Trustees are often paid on an hourly basis, or as a percentage of Trust assets (e.g. 1%), but often less than an Executor/Administrator would be paid in a probate.

Will my estate need to go through the California Probate Process if I have a will?

There are generally 3 types of Wills that may be admitted to probate: Witnessed Wills, holographic Wills and statutory Wills:

Witnessed Wills: Unless the Will is a holographic Will, California law requires that a Will be (see Cal. Prob. Code § 6110);

- Signed by the Decedent (or in the Decedent’s name by someone else at the Decedent’s instruction, or by a conservator under Court order); and;

- Witnessed by at least 2 persons, each of whom a) being present at the same time, witnessed either the Decedent signing the Will or the Decedent’s acknowledgment of the signature or of the Will and b) understand that the instrument they sign is the Decedent’s Will.

NOTE: Even if certain of the above requirements are not met, a proponent of a Will can establish by “clear and convincing evidence” that, when the Decedent signed the Will, the Decedent intended the Will to constitute his/her Will. California Probate Code § 6110(c)(2).

Holographic Wills: If a Will is in the Decedent’s own handwriting, only the Decedent’s signature and the material provisions of distribution must be present for the Will to be valid. It need not be signed by witnesses. If these conditions are met, the Will is called a “holographic Will”.

Statutory Wills: The California legislature has approved a form of a Will, called a “statutory Will”. If a Decedent signed this statutory form and had it witnessed as required in the form, the Will satisfies the California Probate Code requirements for a valid Will.

What Happens If the Will is Lost or destroyed?

If a photocopy of a Will is located, but the originally signed Will cannot be found, California law provides a rebuttable presumption that the Decedent destroyed his/her Will with intent to revoke it.

Cal. Prob. Code § 6124 provides: “If the testator’s will was last in the testator’s possession, the testator was competent until death, and neither the will nor a duplicate original of the will can be found after the testator’s death, it is presumed that the testator destroyed the will with intent to revoke it. This presumption is a presumption affecting the burden of producing evidence.”

The presumption of Cal. Prob. Code § 6124 is rebuttable, meaning that if there is a Will contest, the proponent of the Will (i.e. the person advocating admisIs Prosion of the Will to probate) must introduce evidence that the Will should be validated.

Is the California Probate process private or public?

As a Court process, a probate is largely a public record. With certain exceptions, all filings during the probate are available to the public, including the Decedent’s Last Will and Testament (if Decedent died testate), the Decedent’s assets and financial information, names of the Executor/Administrator and his/her attorney, names of the heirs/beneficiaries, etc.

COMPARE: With a revocable living trust, a probate can be avoided, and therefore so can the public information inherent in a probate.

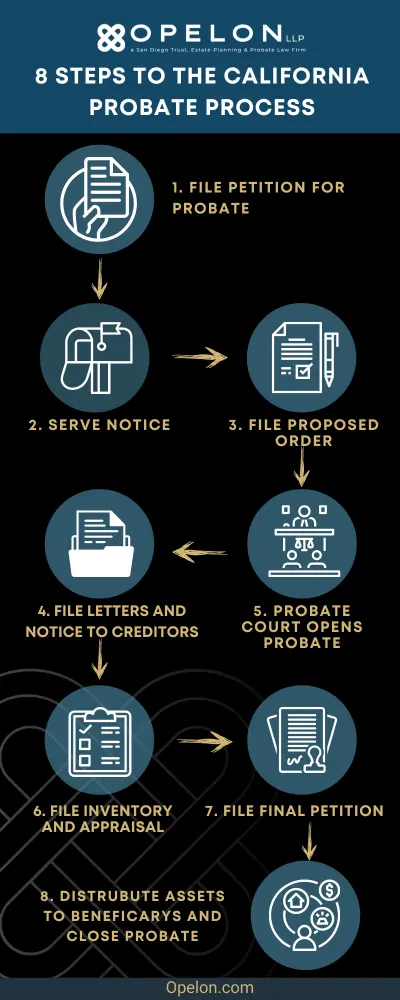

California Probate Process Chart.

What is the difference between Testate and Intestate?

Testate vs. Intestate

A “testate” Decedent passed away having executed a valid Last Will and Testament. The Decedent’s “probate property” will be distributed to the beneficiaries named in the Last Will and Testament.

An “intestate” Decedent passed away without having a valid Last Will and Testament in place. The Decedent’s “probate property” will be distributed to the Decedent’s “heirs at law”. The California Probate Code defines the term “heir at law”. See Cal. Prob. Code § 6401 and 6402. Generally, “heirs at law” are a combination of the Decedent’s spouse (if any) and the Decedent’s:

- Children, if any;

- Parents, if he/she did not have children;

- Siblings, if he/she did not have children or parents;

- Nieces and nephews, if he/she did not have children, parents or siblings; and

- Etc.

What is the difference between an Executor and Administrator?

Executor vs. Administrator

The terms “executor” and “administrator” are the names given to the personal representative appointed by the Court to administer the probate.

An “executor” is appointed by the Court nominated by the Decedent in his/her Will.

If, however, the Decedent died intestate (i.e. without a Will), or if the Decedent died testate (i.e. with a Will) but failed to nominate a person to be in charge of the probate, the person appointed by the Court is called an “administrator”.

Regardless of the name applied to the personal representative of the estate, the responsibilities of an executor and an administrator are largely the same.

COMPARE: A person nominated in a revocable living trust to be in charge of trust assets upon the Decedent’s death is called a “trustee”.

What is the difference between Heir and Beneficiary?

Heir vs. Beneficiary

If a Decedent died testate (i.e. with a valid Will), the person(s) entitled to receive the Decedent’s assets in the probate are called the Decedent’s “beneficiaries”.

If, however, the Decedent died intestate (i.e. without a Will), the persons entitled to receive the Decedent’s assets are determined by California law and called the Decedent’s “heirs at law”. See Cal. Prob. Code § 6401 and 6402.

Generally, “heirs at law” are a combination of the Decedent’s spouse (if any) and the Decedent’s:

- Children, if any;

- Parents, if he/she did not have children;

- Siblings, if he/she did not have children or parents;

- Nieces and nephews, if he/she did not have children, parents or siblings; and

- Etc.

What are Letters Testamentary and what are Letters of Administration in the probate process?

Letters Testamentary vs. Letters of Administration

If/when a petition for probate is approved by the Court and an Executor/Administrator is appointed, the Executor/Administrator must file for and receive from the Court “Letters” (i.e. the document granting powers to the Executor/Administrator).

Without “Letters”, the Executor/Administrator has no authority to act (e.g. marshal assets, pay the Decedent’s debts, pay the Decedent’s taxes, sell assets, buy assets, distribute assets to beneficiaries, etc.); and even with “Letters”, many actions still require Court approval.

The exact name applied to the “Letters” depends on whether the Decedent died testate or intestate, and if testate, whether the person appointed by the Court was named by the Decedent in his/her Will.

- Letters Testamentary: If the Decedent died testate and the person appointed as the personal representative by the Court was a person named as executor in the Decedent’s Will, the personal representative is called the “executor” and must obtain “Letters Testamentary” from the Court.

- Letters of Administration with Will Annexed: If the Decedent died testate, but the person appointed as the personal representative by the Court was not the person named as executor in the Decedent’s Will (or the Decedent failed to name his/her executor), the personal representative is called the “administrator” and must obtain “Letters of Administration with Will Annexed”.

- Letters of Administration: If the Decedent died intestate, the personal representative appointed by the Court is called the “administrator” and must obtain “Letters of Administration”.

What is a Probate Bond and when in the probate process is it needed?

With certain exceptions, an Executor/Administrator must be “bonded” before the Court will grant him/her authority to administer the probate and the petition for probate must reference bond. See Cal. Prob. Code § 8480.

Bond is like an insurance policy; it protects heirs/beneficiaries from an Executor/Administrator who steals from the estate, fails to safeguard assets, negligently manages assets, etc. In these events, the heirs/beneficiaries have a fund (like an insurance policy) from which to recover.

Like an insurance policy, however, bond requires an annual premium to be paid (from estate assets).

Exceptions to the requirement of bond include (see Cal. Prob. Code § 8481):

- If the Decedent died testate and the Will waives bond; and/or

- If all heirs/beneficiaries waive the requirement for bond.

What is the Independent Administration of Estates Act (the “IAEA”)?

The petition for probate must address the Independent Administration of Estates Act (the “IAEA”), and specifically whether the petitioner is requesting full authority under IAEA, limited authority under IAEA, or no authority under IAEA. See Cal. Prob. Code § 10400 – 10592.

- Full Authority: Full authority under IAEA under California Probate Code allows the Executor/Administrator the broadest authority and allows him/her to take many actions without prior Court approval (e.g. sell or purchase real property, sell or purchase personal property, abandon property, borrow against the estate, settlor or compromise a claim, etc.).

NOTE: Even though Court approval may not be required for certain actions, the Executor/Administrator may still be required to give a “notice of proposed action”.

- Limited Authority: Limited authority under IAEA strikes a middle ground between full authority and no authority (i.e. it grants to the Executor/Administrator some of the powers under full authority). For example, an Executor/Administrator cannot sell real property, borrow money by securing the loan against estate real property, etc.).

- No Authority: No authority under the IAEA requires the Executor/Administrator to obtain prior Court approval for most actions.

Bond is like an insurance policy; it protects heirs/beneficiaries from an Executor/Administrator who steals from the estate, fails to safeguard assets, negligently manages assets, etc. In these events, the heirs/beneficiaries have a fund (like an insurance policy) from which to recover.

Like an insurance policy, however, bond requires an annual premium to be paid (from estate assets).

Exceptions to the requirement of bond include (see Cal. Prob. Code § 8481):

- If the Decedent died testate and the Will waives bond; and/or

- If all heirs/beneficiaries waive the requirement for bond.

What is a Notice of Proposed Action in a Probate (NOPA)?

If the Executor/Administrator wishes to take an action under IAEA, but the California Probate Code requires him/her to give a “notice of proposed action” (a “NOPA”) before taking such action, the Executor/Administrator must follow the statutory process found in Cal. Prob. Code § 10580 – 10592.

Specifically, among other requirements, the Executor/Administrator must describe the action he/she intends to take (e.g. sell real property) with a reasonably specific description and the date on or after which the action is proposed to be taken and deliver such notice/description to each heir/beneficiary of the estate.

The NOPA must be delivered to each heir/beneficiary no less than 15 days before the date specified in the notice.

Each heir/beneficiary may then object (in writing) to the proposed action. If, however, no heir/beneficiary objects either within such 15-day window or objects before the action is taken, the Executor/Administrator has authority to proceed with the action.

NOTE: Cal. Prob. Code § 10501 sets forth certain actions that may never be taken under notice of proposed action.

COMPARE: The powers of a trustee of a trust may be specified in the trust or under other provisions of the California Probate Code. In most instances, a trustee has more authority to take various actions than an Executor/Administrator in a probate.

What is a Probate Referee?

During the probate, the Decedent’s assets must be inventoried and appraised, the results of which must be filed by the Executor/Administrator on a form called an “Inventory and Appraisal”. The values for assets such as bank accounts and retirement accounts and life insurance policies payable on death in lump sums can be provided by the Executor/Administrator on the Inventory and Appraisal. Other assets, however, such as the Decedent’s home, other real property, stocks, automobiles, timeshares, etc., must be appraised by an individual called a “Probate Referee” – a person appointed by the Court to provide date-of-death fair market values.

NOTE: Here is a list of to the current probate referees in San Diego.

What is Abatement in Probate?

If there are insufficient assets in the estate to pay the Decedent’s expenses/creditors/taxes/etc. and to satisfy all beneficiaries identified in the Decedent’s Will, the California Probate Code sets forth specific rules as to which beneficiaries see their distributions reduced first. Under Cal. Prob. Code § 21402, “shares of beneficiaries abate in the following order:

- Property not disposed of by the instrument;

- Residuary gifts;

- General gifts to persons other than the transferor’s relatives;

- General gifts to the transferor’s relatives;

- Specific gifts to persons other than the transferor’s relatives; and

- Specific gifts to the transferor’s relatives.”

NOTE: If the Decedent died testate with a Will that directs a different order of “abatement”, the order of abatement in such Will supersedes the above-referenced default California Probate Code order of abatement.

How to file a Petition for Probate in California?

If a formal probate is required, a petition to open the probate must be filed in the appropriate California Court, which, with certain exceptions, is the Probate Court in the California county where the Decedent resided.

This petition must be filed on Form DE-111.

The person to file the petition is called the “Petitioner”. This person is often the person seeking power to administer the estate (i.e. the proposed Executor/Administrator), but this is not always the case.

On the petition, the Petitioner must allege and address:

- The name, residence and citizenship of the Decedent;

- The Decedent’s date and place of death;

- The name and residence of the Petitioner;

- Whether the Petitioner is seeking Letters Testamentary, Letters of Administration with Will Annexed, Letters of Administration, etc.

- Bond;

- Value of Decedent’s probate property / assets, including annual income therefrom;

- Whether the Decedent died testate or intestate;

- If testate, whether the Will waives bond;

- Names of the Decedent’s heirs and spouse, if any; and

- Etc.

Filing Notice of Petition for Probate in San Diego:

Notice of the filed petition, including notice of the hearing date given by the Court, must be served on various parties at least 15 days before the hearing. See Cal. Prob. Code § 8110. Notice must be filed on Form DE-121.

Among other parties who must receive notice are:

- The proposed Executor/Administrator (where the petitioner is not the proposed personal representative);

- If the Decedent died testate, all beneficiaries named in the Decedent’s Will;

- The Decedents’ heirs at law;

- With certain exceptions, if the Decedent’s spouse predeceased him/her, the predeceased spouse’s heirs at law;

- If the Decedent died testate and his/her Will involves a charitable purpose, notice may have to be served on the California Attorney General; and

- etc.

COMPARE: There are generally less notice requirements in a trust administration, California Probate Code 16061.7 being the most common required notice.

Publication of Probate Petition

Cal. Prob. Code § 8121 requires notice of a pending probate petition to be published “in a newspaper of general circulation in the city where the Decedent resided at the time of death, or where the Decedent’s property is located if the court” there has jurisdiction.

The first publication date must be at least 15 days before the hearings.

The probate code states that “three publications in a newspaper published once a week or more often, with at least five days intervening between the first and last publication dates, not counting the publication dates, are sufficient.” Cal. Prob. Code § 8121.

If the Decedent did not reside in a city, or if there is no such newspaper in the city, or if the Decedent’s property is not in a city, Section 8121 provides alternative publication requirements. The information required to be in the publication is in Cal. Prob. Code § 8100.

Hearing on Petition for Probate in California

Upon filing the petition for probate, the Court will set a hearing date for the petitioner (or his/her attorney) to appear before the Court. How soon the Court sets the hearing date varies from county to county.

Theoretically, the Court could set a hearing date 15 days after the petition is filed (15 days being the time required for notice under Cal. Prob. Code § 8110). However, most Probate Courts set hearings between 30 and 45 days from filing.

Provided the petition for probate is properly completed and formalities under the California Probate Code are satisfied (e.g. notice, publication, etc.), and provided further that no interested parties object to the petition, the Court often grants the petition and appoints an Executor/Administrator.

If the Petition is not completed properly, the Court’s “Probate Examiner” will flag “defects” (i.e. procedural issues) that the petitioner must resolve before the hearing. Generally, these “defects” are published on the Court’s website 2-3 weeks before the hearing date. To resolve these “defects”, the petitioner can/should submit a supplement to the petition before the hearing. Some Courts have a prescribed form that can be used for this purpose.

What Are Some of the Common Objections to Petition for Probate?

Common objections to a petition for probate include:

- A party may claim a superior right to act as Executor/Administrator. This right could stem from priority given to such individual in the Decedent’s Will (if the Decedent died testate) or from priority under Cal. Prob. Code § 8461).

- The proposed Executor/Administrator is disqualified because he/she is a minor, subject to a conservatorship, not a resident of the United States, etc. Prob. Code § 8402.

- The Decedent’s Will is invalid because the Decedent lacked capacity to sign the Will, the Decedent was unduly influenced to sign the Will, the signature on the Will is not the Decedent’s, etc. Prob. Code § 8004 and 8252.

- The Decedent’s Will is invalid because it was not signed and/or witnessed by 2 individuals. Prob. Code § 6110.

Regarding a claim that the Will is invalid lacking due execution or witness signatures, a proponent of the Will can overcome the presumption of invalidity upon “clear and convincing evidence” that, when the Decedent signed the Will, the Decedent intended the Will to constitute his/her Will. Cal. Prob. Code § 6110(c)(2).

Request Probate Letters and Order During the Probate Process

Upon the petition being approved by the Court, the Executor/Administrator must then request Letters and an Order appointing the Executor/Administrator.

The Letters will be “Letters Testamentary”, “Letters of Administration with Will Annexed”, or “Letters of Administration”, all depending on whether the Decedent died testate or intestate, and if testate whether the person appointed was named as Executor in the Decedent’s Will. Without “Letters” and an Order, the Executor/Administrator has no legal authority to administer the estate.

What is Marshaling Probate Assets?

Upon being appointed by the Court and obtaining Letters, one of the first tasks of the Executor/Administrator is to marshal (i.e. obtain possession of) the Decedent’s assets. Cal. Prob. Code § 9650. To do so, the Executor/Administrator usually starts by monitoring the Decedent’s mail, forwarding such mail to the Executor/Administrator’s address, reviewing the Decedent’s tax returns, ordering and reviewing the Decedent’s credit reports, interviewing the Decedent’s professional (e.g. legal and financial) advisors, etc.

Once the Decedent’s assets are identified, the Executor/Administrator must then marshal such assets. Regrading tangible, personal property (e.g. artwork, jewelry, clothing, furniture, photographs, etc.), the Executor/Administrator must take personal possession of such property, and if necessary safeguard such assets from theft, damage and waste. With certain exceptions, regarding bank accounts, brokerage accounts, stocks, etc., the Executor/Administrator must re-title such assets in the name of the estate (one exception being retirement accounts). Real property often remains titled in the Decedent’s name until the property is sold or distributed to the estate’s heirs/beneficiaries.

Open an Estate bank account and Apply for a Taxpayer Identification Number

Another “first step” in the probate involves opening an estate bank account (usually a checking account to hold sufficient funds for estate expenses and a savings account for liquid funds over-and-above what is needed for the day-to-day management of the estate).

To open accounts for the estate, the Executor/Administrator must have a taxpayer identification number (“TIN”) assigned by the IRS to the estate. Such a TIN can be obtained online (often in a matter of minutes) by the Executor/Administrator, his/her attorney, or his/her tax return preparer (e.g. CPA or Enrolled Agent).

Conduct an Inventory and Appraisal During a California Probate

During the probate, the Decedent’s assets must be inventoried and appraised (unless waived by the Court), the results of which must be filed by the Executor/Administrator on a form called an “Inventory and Appraisal”. Depending on the asset, the appraisals are performed either by the Executor/Administrator or by the Probate Referee. Specifically:

- Assets appraised by the Executor/Administrator: Cash and cash equivalents (e.g. bank accounts and retirement accounts and life insurance policies payable on death in lump sums) are generally appraised by the Executor/Administrator, the reason being the values of these assets are usually easy to determine.

- Assets appraised by the Probate Referee: Assets such as the Decedent’s home, other real property, stocks, automobiles, timeshares, etc., must be appraised by the Probate Referee – a person appointed by the Court to provide date-of-death fair market values.

Whether or not the estate’s assets are appraised by the Executor/Administrator or by the Probate Referee, the appraisal(s) must be filed on Form DE-160 (Inventory and Appraisal). The California Probate Code and Form DE-160 allows the Executor/Administrator to file “partial” inventories, provided that a “final” inventory is filed within 4 months after letters are first issued to the Executor/Administrator.

NOTE: Depending on the appraisals made by the Executor/Administrator/Probate Referee, bond may either need to be increased or decreased.

Creditor Claims in Probate

The California Probate Code requires the Executor/Administrator to “give notice of administration of the estate to the known or reasonably ascertainable creditors of the Decedent.” Cal. Probate Code § 9050. This “notice” must be given within the later of:

- 4 months after the date letters are first issued; and

- 30 days after the Executor/Administrator first knows of the creditor.

Such notice must be given because all debts of the Decedent must have been paid or adequately provided for before assets can be distributed to the heirs/beneficiaries and the estate closed. Cal. Prob. Code § 11640(a). If the estate’s debts exceed its assets (i.e. the estate is insolvent), the California Probate Code dictates priority of payment for such debts. See Cal. Prob. Code § 11420.

The exact form and substance of such notice is as required in Cal. Prob. Code 9052. Giving such notice on Form DE-157 satisfies these Cal. Prob. Code 9052 requirements.

Once served proper notice (i.e. notice that satisfies Cal. Prob. Code 9052), creditors have a limited period of time to file a “creditor’s claim” against the estate. Specifically, creditors must file their claim with the Court before the last to occur of:

- 4 months after the date Letters were issued to the Executor/Administrator, or

- 60 days after such notice was mailed or personally delivered to the creditor.

If the creditor fails to file a claim within this time, the creditor will, with limited exceptions, be statutorily barred from bringing a claim against the estate (i.e. the creditor no longer will be able to collect his/her/its debt against the Decedent).

How to Respond to Creditor Claims in Probate

For each creditor’s claim filed with the Court, California Rules of Court § 7.401 requires the Executor/Administrator (whether or not acting under the Independent Administration of Estates Act (IAEA)) to:

- Allow or reject in whole or in part the claim in writing;

- Serve a copy of the allowance or rejection on the creditor and the creditor’s attorney; and

- File a copy of the allowance or rejection with proof of service with the court.

Executors/Administrators acting with full IAEA authority may allow or reject a claim without first getting Court approval (unless the claim is a claim by the Executor/Administrator). Cal. Prob. Code § 10552 and 10501.

Executors/Administrators without IAEA authority must file the allowance or rejection with the Court and give notice of the allowance/rejection to the creditor. The allowance/rejection must state (see Cal. Prob. Code § 9250):

- The name of the creditor;

- The total claim;

- The date of issuance of letters;

- The date of the decedent’s death;

- The estimated value of the decedent’s estate;

- The amount allowed or rejected by the Executor/Administrator;

- Whether the Executor/Administrator may act under the Independent Administration of Estates Act (Part 6 (commencing with Section 10400)); and

- A statement that the creditor has 90 days in which to act on a rejected claim.

NOTE: Judicial Counsel Form DE-174 satisfies the requirements of Cal. Prob. Code § 9250.

For allowed claims filed with the Court, the judge will then review the claim and either allow it or reject it. For rejected claims, the Court takes no action; it is up to the creditor at that point to litigate the validity of the claim. A creditor of a rejected claim has 90 days to file such a lawsuit (from the date the claim was rejected) or 90 after the claim becomes due. Cal. Prob. Code § 9353.

6 Possible Exceptions to the Creditor Claim Procedures for Probate in California

The strict timelines set forth above regarding giving notice to creditors and creditors filing a claim may not apply in certain situations, including:

- Known or Reasonably Ascertainable Creditors: A “known or reasonably ascertainable” creditor who does not receive notice of the Decedent’s death under Cal. Probate Code § 9050 is not subject to the strict timelines of other creditors provided notice. The known or reasonably ascertainable creditor generally has 1 year from the Decedent’s death to file a claim. Civ. Proc. Code § 366.2.

- California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS): If the Decedent received or may have received Medi-Cal, or the Decedent’s surviving spouse received or may have received Medi-Cal, notice of the Decedent’s death must be provided to California Department of Health Care Services. Prob. Code § 215. The DHCS then has 4 months after receiving such notice to file a claim. Cal. Prob. Code § 9202.

- California Victim Compensation Board (VCB): If the Decedent has an heir or beneficiary who is or has been confined “in a prison or facility under the jurisdiction of the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, or its Division of Juvenile Facilities, or confined in any county or city jail, road camp, industrial farm, or other local correctional facility”, notice of the Decedent’s death must be provided to California Victim Compensation Board. Prob. Code § 216. The VCB then has 4 months after receiving such notice to file a claim. Cal. Prob. Code § 9202.

- California Franchise Tax Board (FTB): Notice of the Decedent’s death must be provided to the California Franchise Tax Board within 90 days of the Decedent’s death. Prob. Code § 9202.

- Mortgages / Liens on Estate Property: “The holder of a mortgage or other lien on property in the Decedent’s estate, including, but not limited to, a judgment lien, may commence an action to enforce the lien against the property that is subject to the lien, without first filing [a creditor’s claim as provided above] if in the complaint the holder of the lien expressly waives all recourse against other property in the estate.” Prob. Code § 9391.

- Federal Government: Federal law, not the California Probate Code, governs creditor claims of federal agencies (e.g. the Internal Revenue Service).

During a California Probate, What are the Powers of the Executor/Administrator?

The Executor/Administrator will be granted either full authority under IAEA, limited authority under IAEA, or no authority under IAEA. See Cal. Prob. Code § 10400 – 10592.

The power granted to the Executor/Administrator will determine whether he/she has power to take certain actions only with Court approval, without Court approval, or without Court approval provided he/she follows the “notice of proposed action” procedure.

NOTE: Whether or not an Executor/Administrator is granted full or limited IAEA authority, a Decedent’s Will may preclude various actions without Court approval.

California Estate Taxes

All of the Decedent’s debts must have been paid or adequately provided for before assets can be distributed to the heirs/beneficiaries and the estate closed. Cal. Prob. Code § 11640(a). Included in these debts are the Decedent’s and the estate’s taxes.

Among other tax returns that may have to be filed (with potentially taxes owed) by the Executor/Administrator before the estate can be terminated are:

- The Decedent’s personal income tax returns, on both a state (e.g. Form 540) and federal level (e.g. Form 1040);

- The estate’s “fiduciary” income tax returns, on both a state (e.g. Form 541) and federal level (e.g. Form 1041); and

- A federal Estate Tax Return (e.g. Form 706), if the Decedent’s taxable estate exceeds the estate tax federal exemption for the year of the Decedent’s death.

Final Stage to the Probate Process: How to Close a California Probate?

The Final Report and Petition for Final Distribution:

Once the Decedent’s debts and taxes (if any) have been paid by the Executor/Administrator, the estate may be in a condition to be closed. The Executor/Administrator will file a Final Report and Petition for Final Distribution. In this Report and Petition, the Executor/Administrator is required to:

- Account to the Court and the heirs/beneficiaries, in which the Executor/Administrator sets forth all assets that existed at the start of the probate, all receipts and property received during the probate, all gains on sales of assets, all disbursements made and expenses incurred during the probate, all losses on sales of assets, all distributions to heirs/beneficiaries, and all assets that exist as of filing the Report and Petition.

NOTE: If all heirs/beneficiaries waive an accounting, the Executor/Administrator may not be required to present the above-referenced accounting in the Report and Petition.

- Confirm that proper notice was provided to known and reasonably ascertainable creditors and to the California Department of Health Care Services, California Victim Compensation Board, California Franchise Tax Board, etc.

- Confirm that the Probate Referee was paid his/her fee and the date it was paid.

- Indicate whether the estate is solvent or insolvent.

- Confirm that all estate assets have been filed and appraised on the Inventory & Appraisal.

- Report what creditor claims have been filed and resolving such claims.

- Report what actions were taken by the Executor/Administrator under his/her IAEA.

- Report whether income taxes, estate taxes, or property taxes are due or payable or have been paid.

- Indicate what statutory and extraordinary fees (if any) are being requested by the Executor/Administrator and his/her attorney, and the calculation of such fees.

- Request approval to distribute assets remaining to the heirs/beneficiaries.

When to Distribute Assets to Heirs/Beneficiaries

If/when the Court approves the Final Report and Petition for Distribution, the Executor/Administrator will have authority to distribute assets remaining in the estate to the heirs/beneficiaries.

If the Decedent died testate, the distributions made would be to the beneficiaries set forth in the Decedent’s Will, under the specific amounts and/or in the proportions set forth. If the Decedent died intestate, the distributions made would be to the Decedent’s heirs at law, as set forth in Cal. Probate Code § 6401 and 6402. Generally, “heirs at law” are a combination of the Decedent’s spouse (if any) and the Decedent’s:

- Children, if any;

- Parents, if he/she did not have children;

- Siblings, if he/she did not have children or parents;

- Nieces and nephews, if he/she did not have children, parents or siblings; and

- Etc.

Upon making such distributions, the Executor/Administrator will then need to file receipts with the Court signed by the heirs/beneficiaries acknowledging their receipt of the distribution(s). Finally, the Executor/Administrator will need to file an Ex Parte Petition for Final Discharge and Order. This Petition for Discharge and Order is important because it discharges the Executor/Administrator and releases him/her from liability for subsequent acts.

Should you use a probate attorney for the probate process?

The Probate Process is a very technical and time-consuming process. This ultimate guide to probate is intended to give you a better understanding of the process, however, it is not intended, and should not be used, as legal advice. We strongly recommend that you work with an experienced San Diego probate attorney to shield yourself from personal liability and make the process as efficient as possible.

Keep in mind that prior estate planning with a valid revocable living trust, power of attorney, and advance health care directive will help you to avoid probate altogether.